Toxic

The word toxic is everywhere. We use to describe all sorts of things we don’t like, from bad relationships, to vast slices of our culture. But have we overused the word? It’s time to ask what we mean by toxic and why we use it so much.

I’m a sucker for a good bit of detox marketing. Cleansing herbal teas, face creams, smoothies, or spa treatments: just put “detox” in the name and I’m instantly willing to hand over the cash.

Detox is such an alluring concept. Detox appeals to the thought — let’s call it our intuition — that behind our tiredness, our struggles to stay fit, our ever-changing moods, or just the dark circles under our eyes, there’s something wrong with contemporary life, something toxic.

So, hand me a smoothie, book a massage, and let’s get rid of the toxins!

Toxic Goes Mainstream

The idea of toxicity started becoming popular in conversations about the consequences of excess. Detox used to be code for “I think I need to stop drinking and start eating healthily for a while” and maybe “get a few good nights’ sleep.” Then, influenced by alternative medicine and healthy living movements, the concept broadened, intensifying our wariness of industrialised food and our obsession with work-life balance and happiness.

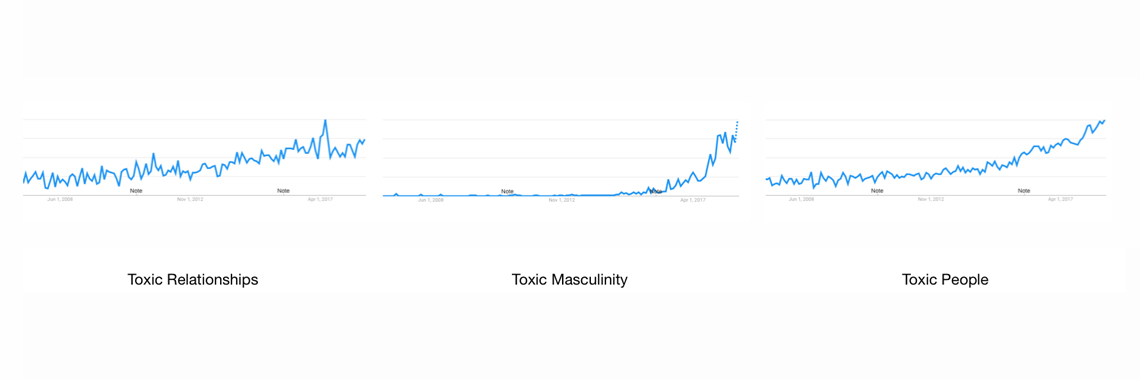

In recent years, we’ve found new uses for the word “toxic.” “Toxic” describes more than just something that we need to purge from our body; now it describes something wrong in other people, a fault or defect, that negates their right to speak in public or to hold a position of authority or influence.

Defining Toxic

We hear this word a lot now. But what does it really mean? Sure, some people’s harmful behaviour is so contagious that the word toxic feels apt. We’ve all encountered people, often in workplaces, who seem to poison the air around them. It’s not just the wrong they do; it’s the way their wrongdoing gives permission for others to do wrong as well. It’s infectious.

Let’s consider how the phrase “toxic masculinity” has taken off. A lot of bad male behaviour — bad things men do to women, bad things men do to children, bad things men do to other men — happens within a culture that enables and facilities such conduct by providing ready-made excuses and explanations. Not only do these justifications let some men get away with bad actions; men who might not otherwise have behaved badly cover for, and are complicit in, those actions. It’s not one bad fruit but a bad way of farming.

So, we add the label “toxic.” It seems to say a lot. But, in a way, it doesn’t say much more than “bad.” As we wonder where to draw the line between toxic and non-toxic masculinity, our energy is diverted from asking deeper, more immediate questions about masculinity and about the generations-old but increasingly impoverished definitions of what it means to be a man.

The word “toxic” feels powerful, but it isn’t precise.

We don’t even have an agreed definition. Without one, it’s hard to create strategies to fix the problems we label as toxic. There’s a vast difference, for example, between suggesting someone is toxic and suggesting they are narcissistic. And, while we can meaningfully talk about how to make our culture (including our ways of educating young people, or sharing our identity) less narcissistic, making a whole society less toxic sounds like an impossibly vast task.

Our Toxic Times

Ours is rapidly becoming a censorious time. We are uncomfortable listening to or engaging with different viewpoints. Maybe we are collectively overwhelmed.

As the impulse to label people as toxic hardens into a reflex, we have started to say some people’s toxicity means they have no right to a voice—which in our digitally mediated age, feels awfully close to saying they have no right to exist. If we say whole classes of people don’t deserve to be part of our society, maybe it’s time to consider how close we are to a dark moment in history.

I believe in a notion of justice where wrongs are made right, where illness can be healed, where lives can be redeemed. And I’m not sure the notion of toxic is compatible with that.

Sure, some actions are toxic, but are we saying those wrongs cannot be made right, that there is no justice for some misdeeds? Yes, some people are toxic, but are their maladies incurable? Yes, some people’s lives are marked by patterns of toxicity, over many years, but does that mean they cannot change, or at least do some good with the time they have left?

A Slow Glass of Detox in A New Ethical Age

I stare out the window waiting for the timer to sound. When it does, the cup of detox tea, packaged in a reassuringly green box, will be ready. I feel a little overwhelmed. These days when summer makes an unwelcome encore appearance well into autumn have always done that to me, though I’m prone to blame it more on digital, rather than temporal, intrusions these days. I’m glad for the cup, even if I doubt it will do anything to my toxin levels. It makes me feel good.

Writing this piece has been tough. All writing is tough, but this piece asked me to wade back into waters—into questions of culture and morals—that I’d left behind, at least in my writing.

For a long time, it seemed we couldn’t have ethical conversations. Talk of morals was tantamount to delivering judgements. We were so scared of feeling shame or guilt that we had to pretend that human conscience was some kind of historical throwback, almost a religious relic.

For a long time, the daily news cycle was mostly economic analysis bookended with the occasional national disaster, regional conflict, minor political controversy or, on a quiet day (and there seemed to be so many), some celebrity gossip.

But now everything feels more urgent.

The standard journalistic move that served a generation—take two sides of an argument, put them up against each, shrug as if to suggest “Who knows?” then ask “What do you think?”—now just produces rage.

What Do We Do With Our Anger

What we have now is anger and outrage seeking categories to think within. “We’ll show them at the next election” is a fine sentiment, but then what? If we’re going to make things better, we need to talk about what good means. Same for right, true, just, and fair. All these words need substance. Otherwise, they’re mere slogans.

Popular culture, even high culture, seems impotent right now, precisely because it has so often been evacuated of ethical language. To point and mock, to ridicule, is not the same thing as to articulate a better way.

The art of living well has for too long been code for the art of consuming impressively. This has to change. Perhaps the best examples we have of this now are people trying to live more sustainable, ecological lives. But we need more than life at peace with nature. We need life in harmony with each other, an ecology of humanity.

If we really are entering a new ethical age, then we’re going to need sharper, more focused words. Toxic just doesn’t puncture anymore. It bounces off the hard shell of sectarian daily controversy.