Is Expatriate A Dirty Word

The word expat, or expatriate, is becoming unpopular. But should we stop using it?

I am an expatriate. Although I’m an Australian citizen, I left Australia (where I grew up) in early 1999 and since then I’ve lived in the UK, India, Hong Kong and now Singapore. I believe life tastes better when mixed with a little adventure and my big adventure is trying to figure out how to live (and live well) in a different cities around the world.

Although I’ve frequently used the term expatriate to describe myself (as I did in the paragraph above), I’ve started to wonder if the word carries troubling negative connotations. Recently, a comment on Twitter suggested expatriate was an offensive term. That promoted me to ask for different readers’ views, which elicited a full range of responses, from the casually positive to downright negative.

Reading those opinions made me question my own use of the word. On the one hand, I have no problem with using expatriate in the classic, dictionary sense, as a person who literally lives (ex) outside their homeland (patria). But, on the other hand, in every city I’ve lived there are places – pubs, clubs, shopping districts, even whole neighbourhoods – where expats tend to congregate. Those tend to be places I seldom, if ever, visit.

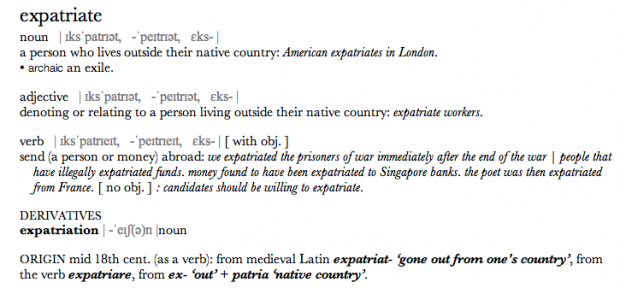

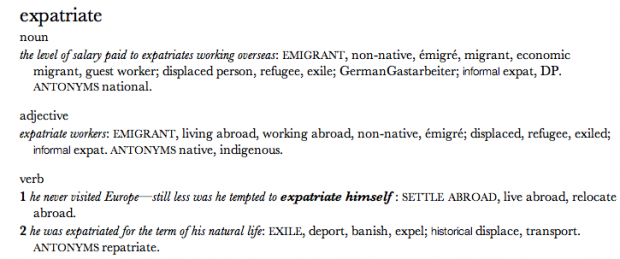

Dictionary Discontinuities

Look up expatriate in most dictionaries and you get a fairly straightforward technical definition; someone who is living in a different country to the one in which they were born (or brought up in). But, once we search a thesaurus, different definitions pop up, reflecting the various ways the word expatriate has been used down the years.

Emigre Or Immigrant

One fascinating response on Twitter suggested some use expatriate to denote a person’s lack of loyalty to their home country. Certainly this has some history in the USA, where there was a law in 1868 that defined expatiation as the right to renounce one’s citizenship. Prior to this the common understanding was, a person had perpetual allegiance to their place of birth, even if they chose to move to another country. This was one of the reasons the US went to war with England in 1812, after the British Navy started seizing former sailors who had left to become Americans, working on American merchant ships.

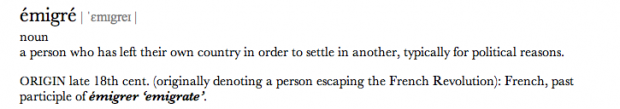

These days, we tend to associate the right to renounce one nationality and take up another as a common part of naturalisation and citizenship, something immigrants go through all the time in many countries around the world. Their reasons for doing this are many and varied. The specific idea of rejecting your home country for political, religious or ideological reasons is best summed up in the less commonly used word, Émigré.

There’s a frequent confusion between the words emigrant and immigrant. The semantics point to a real difference, one starts with e, the other with i, in the same way that exterior and interior are both very distinct words. An emigrant is driven by their desire to leave a place, whereas the immigrant is driven by the desire to go to a place. These differences in motivation will shape the way each settles into their new home and the way they will carry the culture and traditions they bring with them.

Expatriate Elitism

Unfortunately, there seems to be a class-ist (and occasionally racist) element to the way some people use expatriate to denote wealthier, more educated foreigners with high paid jobs and lavish company benefits, in contrast to foreigners with lower paid jobs who might be called, foreign workers, or simply immigrants.

Like any generalisation this has some truth to it, but the reality is not as simple, or straightforward. Not everyone who has a corporate job is the beneficiary of all the supposed expat perks, like generous housing or education allowances. And, not all those who are highly educated (especially in the education and NGO sectors), are living it up with huge wages and bonuses.

When I lived in Delhi, those on corporate assignments made up around a third of the expat community. The other two thirds were on diplomatic assignments, or working with NGOs. There was no single expat lifestyle, but rather a spectrum of different ways of living and integrating with local culture. While there are more “corporate” expats in Hong Kong and Singapore, the same spectrum of ways of living applies.

Opportunity

The expat that exists in many people’s minds is simply an increasingly fictional caricature. Some people become expats as a way to leave a country they no longer identify with, or because of the opportunity to do some business and make money, their motivation could be humanitarian, it might a voyage of self-discovery, a cultural adventure, or perhaps they are just following their heart, having fallen in love with a foreign land, or someone living in that land.

It’s the opportunity that drives people to become expats and this will be different from one expat to the next. The opportunity may also change over time as people’s lives and passions change. And, for some trailing spouses and kids, the reality may be the opportunity wasn’t actually theirs and the challenge becomes finding the sense of opportunity after they have moved to a strange land.

The varied nature of the opportunites at the heart of each expat experience also explains why expats respond to being in a foreign land in such varied ways, from passionate engagement with local culture, through to tentative, or even stand-off-ish postures.

Glocalisation

Whatever the opportunity might be, expatriates have always been byproduct of globalisation. And, increasingly, globalisation is being defined by a two step process, as the world simultaneously becomes more global and more local.

Think about McDonalds, which is always the poster-child for globalisation. Sure, McDonalds is standardised around the world. But, as any frequent traveller will tell you, McDonalds introduces variations in different markets, to suit local tastes. Eating McDonalds in India, with McAloo Tikki, Chicken Maharaja Mac and McSpicy Paneer burgers is not the same as eating McDonalds in the US!

And, while globalisation adapts to local tastes, it also creates a gulf between those who participate in the global economy and those more tied to local careers. In London, I knew expats who worked in the head office of their company and regularly dealt with fellow employees in New York, Tokyo or Frankfurt, but seldom, if ever, with employees from other offices in the UK.

Equally, an expat who is sent to work in Melbourne may likely find their next job is in Shanghai or Seoul rather than Sydney or some other Australian city. The same is increasingly true for education professionals who might move across borders from one university, or international school to the next.

Resentiment

Having a globally mobile pool of talent, who are perceived as living a life of luxury and privilege, can create a backlash at times, especially when fuelled by populist politics. Read the comments made against expats online and it’s not hard to see the tinge of resentiment coming through people’s words. Not just the sense of carrying a past hurt, but the deeper feeling of hostility, frustration and even jealousy that Kierkegaard and Nietzsche wrote about.

In a way, expatriates can become the scapegoat for a lot of discontent over the effects of globalisation and in particular, what some see as the erosion of local customs, traditions and even environments.

The Ugly Expat

Just like the cliché about the ugly tourist, there are also ugly expats. Boorish, prone to anger, quick to rant about how their home country does everything better, unwilling to learn local customs while living and socialising in ghettos with fellow expats.

I knew an expat in Delhi who only left his diplomatic compound to play golf or head to the airport. Another time an expat cornered me to ask about life in South America, since his work was offering a post there. I assumed his question would be about culture, or maybe safety, but it turned out he only wanted to know about the cost of domestic staff, because wife would only like to move if the help was cheap.

These kinds of expats can be used to fan the flames of resentiment by those who want to cry, “they’re ugly, they’re overpaid and they’re over here.”

Acknowledging the Issues

While not wanting to excuse bad behaviour, what you see in populist rants seldom acknowledges the issues involved in adapting to a different country, language and custom. The reality on a day to day level is even more complex than many might assume.

Change countries and everything is different. Opening a bank account and getting utilities connected in the UK was an ordeal. In India we could find familiar brands of breakfast cereal but, because they were made to be consumed with hot milk, they were very different to what we were accustomed to. In Hong Kong it didn’t take me long to realise some taxis operate in some parts of the city and others don’t based on their colour, but it took me a lot longer to figure out that red taxis work both sides of the harbour and may, or may not take you from one side to the other.

But, these concerns are minor compared to the emotional issues that arise from being far away from friends and family, having a spouse who is often travelling, or working very long hours and helping children adjust to life in a foreign land (although sometimes the kids adjust better than the parents).

Every expat I’ve spoken to has a horror story (often from their early years) of being ripped off, mistreated, yelled at, or simply struggling to cope with the stress of adapting to a new place. But, almost of all them will counter those stories with many more about the wonderful experiences they’ve had and the things they’ve learnt about themselves, the cultures they have been exposed to and the humanity we all share.

Paths To Migration

Nothing pulls the status of expatriates into sharper focus than asking what happens if they choose to stay in a place. After all, we started by looking at a fairly strait-forward dictionary definition, which implied being an expatriate was a temporary state of affairs. If someone chooses to stay in a new country after five or ten years then haven’t they really immigrated, especially if they have no plans to leave?

I’ve often pondered this while talking to expats, especially in Hong Kong and Singapore, who have permanent residence and deep passion for the new homelands. Of course, in neither place is the path to citizenship clearcut (and even the rules around permanent residence keep changing). Most will openly wonder if they will ever be accepted as locals, no matter how long they stay.

Any country that does not offer permanent residents a clear path to citizenship will perpetuate a state of foreignness amongst those within its borders and potentially breed resentment between locals and those who wish to be locals.

Truth Is – We All Live In A Bubble

Another common complaint lobbed at expats is that they live in a bubble. To some extent this is true. And, for some of the reasons I’ve discussed, it’s inevitable, at least in part and up to a certain point. But, the truth is we all live in bubbles, which is a way of saying we all live in cultures and societies that pre-date our arrival and shape our outlook.

It’s just that when we encounter people who come from a different bubble it makes us ask questions, about them, about ourselves and about the whole, epic, multi-thousand year experience of bubble-making; or as it is commonly called, human civilisation.

“We are the stories we tell ourselves”

Shekhar Kapur

Which is why, when we use a word like expatriate (or local, immigrant, foreigner or tourist) it says just as much about us as it does about the person we are describing. Words are just vessels we fill with meaning based on our experiences, ideas and predispositions.

I’m not about to stop using the word expatriate. I still believe it is a useful technical term in this age of a globally mobile creative-class. But, I have to recognise it is a fraught word, which is open to many different interpretations.