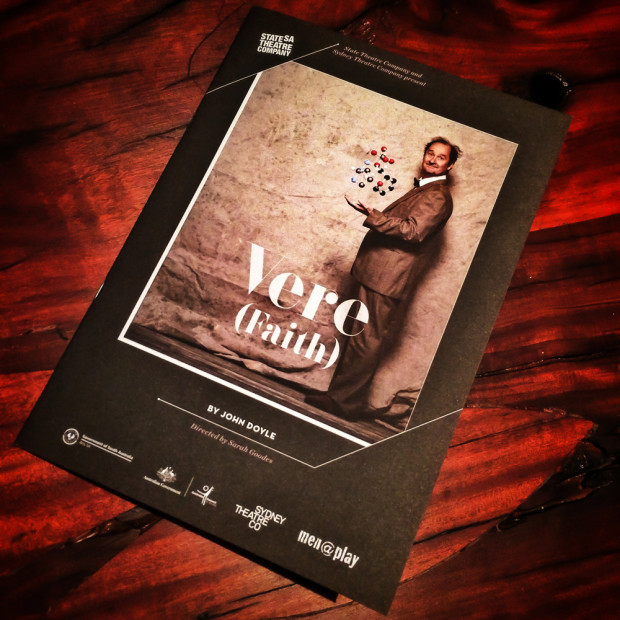

Vere (Faith)

“It has been surmised that the [Catholic] Church supported the Labour Party in the hope of concessions in the matter of education. The chief political aim of the Romans is certainly to secure a subsidy for their schools from the State. The hierarchy maintain that the State secular schools are unchristian, and that is impossible […]

“It has been surmised that the [Catholic] Church supported the Labour Party in the hope of concessions in the matter of education. The chief political aim of the Romans is certainly to secure a subsidy for their schools from the State. The hierarchy maintain that the State secular schools are unchristian, and that is impossible for the faithful to allow their children to be educated in their godless atmosphere. They have fine schools of their own, but the priests argue that it is unjust that their flock, who contribute to the upkeep of these, should be taxed for the support of the State schools, which they cannot use. They, therefore, claim a Government subsidy for their sectarian institutions.”

Those lines are from How Labour Governs: A Study of Workers’ Representation in Australia, written in 1923 by Vere Gordon Childe, better known as V. Gordon Childe. Born and initially educated in Australia Childe went onto graduate studies at Oxford.

But, after returning home he was unable to hold down an academic post in Australia, because of his socialist ideals. Childe eventually made his way back to the UK, carving out an extraordinarily successful academic career as an archeologist, becoming one of the most published (and translated) scholars of his time. Childe was even mentioned by name in the film Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull.

Vere (Faith), a two act play, is based on a fictional scientist called Vere, a namesake of Vere Gordon Childe, who is approaching the twilight of a distinguished career. Vere is about to take a summer sabbatical to the particle physics laboratory CERN, to observe research into the Higgs Boson particle.

But, on the eve of his departure, before celebratory drinks with his university colleagues, he receives a shocking diagnosis. Vere has advanced dementia. His academic (and personal) future is in doubt.

Vere (Faith) was written by John Doyle – a well known Australian comedian. Doyle shot to prominence in the mid 80s with This Sporting Life, a long running radio programme, co-created with Greig Pickhaver. This Sporting Life savagely satirised the world of sports and sports commentary, with a largely improvised, yet skilfully crafted weekly broadcast.

This play, Doyle’s second, was inspired by Doyle’s own experience caring for his father, who was suffering from a severe form of dementia. Doyle is an Atheist, though also a product of a Catholic School education. He acquired an interest in Vere Gordon Childe while filming a TV series near the archeologist’s former home.

Much of the first act of Vere (Faith) sees the professor and his colleagues sharing drinks, telling stories and for the most part, enjoying some bawdy banter. This act is fairly conventional stuff; the lecherous old Vice-Chancellor, the sycophantic younger scholar, the frustrated female Assistant Professor, the awkward but gifted computer scientist, the deer-caught-in-the-headlights young student. The jokes are not memorable but they come often enough to keep the pace moving along.

Vere himself (along with the Vice-Chancellor is his less lewd moments) is possessed of a superior intellect, a grasp of ideas far beyond the confines of his academic specialisation. His mind is nimble and able to slip from poetry to politics to physics and back again. But, there are moments, clear enough for all in the room to see, when he struggles with clarity of thought. Something is not quite right.

Near the start of the act, the student asks Vere to sign a copy of Vere Gordon Childe’s How Labour Governs which has been autographed not only by the author himself, but also another famous Australian Vere, Herbert Vere “H.V.” Evatt, a mid-20th century Australian Jurist and Politician, considered by many to be one of the most intellectually able men to enter public office in Australia.

With this kind of a set up, one would be forgiven for expecting the second act to put the professors decline in the context of the role of intellectuals in Australian public life. After all, Professor Vere is one of a trinity of “great Veres” as they are called in the play. But, as we have already been told in the play’s notes, Vere (Faith) has other, more theological aims.

As the second act opens, we see Vere’s health has clearly deteriorated. It’s moments before a dinner party and Vere has soiled himself. What follows is a dishearteningly long series of scatological jokes which, sadly, set the tone for much of the rest of the play.

Vere’s grandson is engaged to be married and the dinner party is set for a meeting of the two families. Vere’s son is an economics lecturer, a rationalist, the father of the bride, a priest and a bit of an idiot, really. One expects a Molière-like grand farce, satire used in the service of reflections on life, death and the meaning of it all.

But, the play simply fails to deliver on this promise. The opportunity to explore the role of the public intellectual is foregone, the debates on religion versus science are silly and trivial, the general tone conservative and the humour, if it can be called that, parochial and cruel.

If the second act has any redeeming moments, they all belong to Vere (wonderfully brought to life by Paul Backwell). As Vere struggles to find mental clarity, he breaks into the ruckus with moments of real kindness, a beautiful instant with his son, a startling realisation about his grandson and a tender exchange with his future grand-daughter-in-law.

Vere seems to have collected around him some precious tokens of the life he has lived; a neolithic axehead, which serves a talking point for the wonder of imagination, a notebook he shared with Peter Higgs (of the Higgs-Boson particle), a bottle of rare wine given to him by the Prime Minster on the occasion of gaining a scholarship to study in the UK, a bracelet his deceased wife wore when they were courting and a first edition copy of Robert Hooke’s Micrographia.

The latter he tries to give to this grandson’s fiancé. She appreciates the gesture and how much it means to him, while everyone around can only focus on the commercial value of the book. Earlier in the act, a painting belonging to Vere had been similarly reduced to dollars and cents, as the characters clearly had little intelligent comment to make, beyond the insured value of the work.

Vere (Faith) raises so many issues that are ripe for either satire or discussion, but doesn’t give the issues, or most of the characters, the space to develop. Beyond Vere’s moments of clarity, it is a bleak theatrical experience.

Having retired in 1965, Vere Gordon Childe set sail for Australia once more. He was all too painfully aware of his quickly diminishing academic prowess. Upon returning, The University Of Sydney, which had refused him work for his political beliefs four decades earlier, granted him an honorary degree. The natural beauty of the countryside moved Childe deeply. But, he was quickly disillusioned with Australian culture, finding it racist, reactionary, anti-intellectual and increasingly suburban.

Childe ended his own life, falling from Govett’s Leap to his death. Vere (Faith) echoes this tragic end but, sadly, lacks the courage to fully explore the disillusionment Childe experienced.