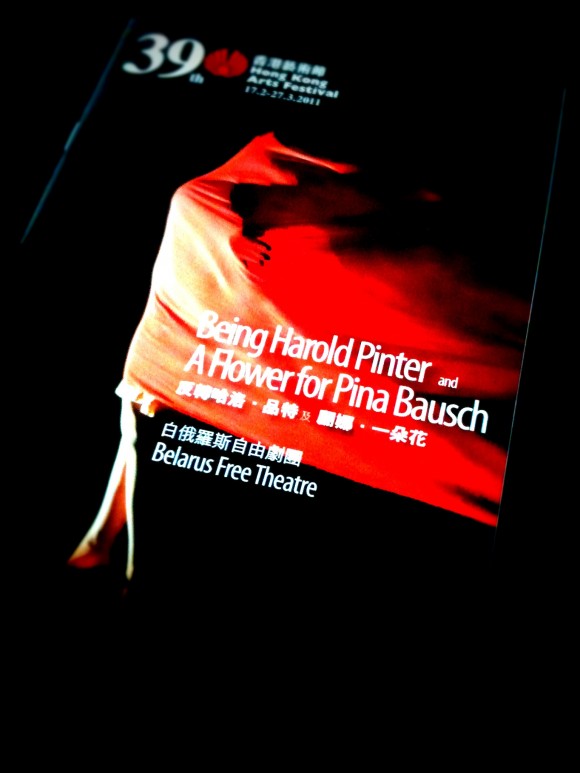

Being Harold Pinter

Is truth in art the same as truth in everyday life? That question animates many debates about the role of politics in art; be it photography, music, film a or theatre. That same question forms the core of the Belarus Free Theatre’s daring production, Being Harold Pinter. This is a controversial and critically acclaimed work, […]

Is truth in art the same as truth in everyday life? That question animates many debates about the role of politics in art; be it photography, music, film a or theatre. That same question forms the core of the Belarus Free Theatre’s daring production, Being Harold Pinter.

This is a controversial and critically acclaimed work, as you can gather from reviews in The Guardian, The Telegraph, The New York Times and Variety. I managed to see it on Wednesday night and was very impressed (as was local blogger HKarts).

Being Harold Pinter is a sparse, dynamic and engaging one act play, that interweaves sections of Harold Pinter’s Nobel prize acceptance speech with scenes from his plays and also testimony from eyewitnesses to Belorussian political oppression.

The staging, makeup and costuming were minimal and the effects simple – an apple being crushed to simulate oppression, a plastic sheet thrown over the cast to simulate drowning, small shoes to suggest the vision of a child being attacked. But, the performance was powerful nonetheless. This kind of theatre reminds us that simple ideas (like a small flame moved over a naked body to suggest torture) can still be harrowing if well implemented.

That said, most of the focus was on the action and dialogue (which was a little difficult to follow as at times the sur-titles were out of sync with the dialogue). Pinter’s words were delivered with an intensity and ferocity that was missing from productions I have seen in the past.

That the Belarus Free Theatre chose to interpret PInter’s works that way was interesting. A common criticism of Pinter suggests that his plays didn’t always make as clear and forceful a political critique as his speeches and other writings away the theatre.

But, Being Harold Pinter underlines how Pinter always scrutinised – in an unflinching way – the human condition. Such explorations allow us to reflect on politics, especially the politics of oppression and otherness. This is the same reason why Shakespeare’s best plays are as politically potent and relevant today as when they were first staged.

For example, in the 2003 production of Henry V at The National Theatre in London (with Adrian Lester in the lead role), the drama is moved to a contemporary setting, with the action being constantly filmed and played back on FoxNews like screens. The famous St Crispin’s Day speech is delivered in a tone of dry cynicism, played to camera, for effect.

This kind of political challenge that doesn’t come from a shrill and direct evocation. Great art is political when it most deeply addresses the human condition and, of course, when it does that it is never just about politics. That re-imaging of the St Crispin’s Day speech works because Henry V is about a lot more than just politics and the fact that Shakespeare wove theology into the narrative leaves an opening for us to think about how religion is used in social discourse in ways that transcend the original “truth” of the play.

Being Harold Pinter was similarly transcendent. Although we do not live within the exact political context of the actors or speak their language. The essential truth of their drama touches us because we understand that the seeds of anger and repression find root in the everyday of our own lives and we know that political oppression exists in our own region of the world.

And, when we realise that, this work from a another place and another context can address us so clearly we experience the truth of art.